If you have never heard of the Pareto Principle or Parkinson’s Law, get ready for a potential re-framing of how you tackle lighting work from this point on. On Stage Lighting uncovers a key secret ingredient to enlightenment through lampie-Jedi knowledge, and to improving your effectiveness as a lighting programmer. Partly though using a concept named after an obscure Italian economist.

OK, so those of us in UK Higher Education have fallen over the line for another year and some students (almost) have their degrees in their hands while others are a few more steps closer. What does that mean in the dusty offices of On Stage Lighting? It means that I actually have time to write something other than academic documents and student feedback. Having pretty much dealt with a load of key lighting design and practice topics over the years, it is less often that this site sees new stuff, not least because we don’t believe in publishing for the sake of it. Today is no exception and for the feed readers of OSL, the new-stuff servers have been restarted for a very special reason.

Today, we are going to look at two ideas that have the power to increase your knowledge as a budding lighting Jedi and generally make your life better, improve your chances with the person of your dreams etc. (OK, maybe not that last one). We need to think about the two generic ideas. Then we need to apply them to our world as lighting designers, programmers, and technicians.

Parkinson’s Law

The first ‘thing’ in the pantheon of ‘be really good skillz’ that we need to apply to our lampie selves is Parkinsons’ Law. In my experience, this is as relevant to the production of shows as it is to all the other management-y stuff you can read about on the internet. There is a version that I find particularly helpful in framing what Parkinson’s Law is all about. It goes something like:

“Time wasted is proportional to time available.”

Other versions of the Law are about how work expands to fit the time available , blah, blah but basically, what we should care about is time being WASTED. The more time you have, the more time you waste – as many of my students would probably testify. Different elements of the entertainment industry vary, in my experience, as to how much fat there is in any production task or scheduled project. Some of this is down to culture and some depends on individuals. The On Stage Lighting challenge for you is to use your knowledge of Parkinson’s Law to be leaner and meaner and, frankly, head to the pub earlier.

The Pareto Principle

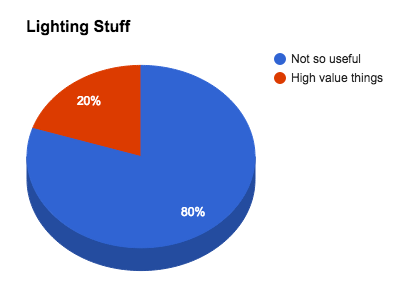

Also referred to as the 80/20 rule , this old idea returned to the spotlight through western productivity culture on the ‘net in the 2000’s and was named after an economist named Vilfredo Pareto . A few people that know me well enough will also know that 80/20 is a big part of my working life and this article asks you as an On Stage Lighting reader to consider how it applies to your lighting practice. The basics of the principle are sometimes described as:

“80% of the outputs result from 20% of the inputs.”

What the Pareto Principle suggests is that a only a proportion of what we actually have or do is producing the lion’s share of what we end up with. When it comes in conjunction with Parkinson’s Law, one can also turn this its head and speculate that 20% of the result takes up 80% of the time, for example. Time more or less wasted.

In reality, these numbers are pretty arbitrary. One may equally argue for 90/10 or 99/1. No matter, it’s the idea that is important.

So what does all this have to do with stage lighting?

Programming Productivity

If you have been following along so far, you may already have your own answer to why the Two P’s are relevant in lighting and more specifically in lighting programming. Let’s be totally honest with ourselves and consider a typical programmers scenario for a one off concert multi-act event. You rock up (or fall into the control position, having just completed a mega-rig and snagging session) with an idea that you need a load of stuff in the desk for the show tonight:

You start by programming Groups, add some extra permutations and even end up saving “DSR Ladder Washes Only Even Minus the Top One” – just in case. You never know when you might need that group. Now it’s palettes time. The basic colours are already in but hell, you aren’t the kind of programmer that feels worth your money if you simple rely on O/W, Red, Blue and the like. No, you must program up some additional colours. Oh, and sort out a load of gobo spins in all directions – just in case. Colours and Beams – plenty of.

Position palettes up next, again the first five are just a warm up. You end up with twenty permutations, including six different audience positions. Now the fun starts. You love programming FX right? Chases? Well, sure, we don’t just want boring ol’ Intensity Masters, we need combinations and pairings and a stack of 6 chase orders to mix it up a bit. Don’t want the show getting dull for the punters, eh? They notice the order in which your PARs flash, right? Movements various – Sweeps, Circles, Funny In and Out-y things – they are all going in there. “How many playbacks has this desk got? Do we have access to a wing?”

At this point, we are assuming that you aren’t a primarily theatre programmer and already get the fact that you are not trying to program cues (lord help you) but stuff that you can add together to make myriad looks on stage throughout the night. That is to say, you are already familiar in the ways of the concert busking world. If that was a big assumption, just stop trying to make full cues right now and go and read Concert Lighting Programming in 30 Minutes. Better? OK. Making full state cues (and making a lot, so the audience don’t get bored) is not the order of the day for this one. Incidentally, this particular way of thinking is quite a big transition for learners coming from their first forays into working with a lighting desk on theatre shows, so it’s not a big deal.

Back to the programming. Right, it’s doors. You skipped catering and are busily checking a few things in blind while the place fills up. When programming for a show tonight, the only thing that will stop you programming is, well nothing up to and including the show actually starting. “Hey, this number is a slow one, I can easily squeeze in some additional strobe playbacks in Blind while this One-Look-Song grinds on right?”

Only once you have run the show does it become apparent that 80% of the actual show is made up of 20% of the programming – or worse. If you were honest with yourself, you could have actually used that lot for the 100% of show and it may have been easier to access as the good stuff (AKA the stuff that you remembered you could actually use and make work) wouldn’t be spread across 50 playbacks and mixed up in that stack congaing the PAR chase, the steps of which you based on the square root of ?1 , In and Outs.

If you were lucky, you actually only had 30 mins of programming time. Parkinson’s Law sats that having 4 hours would likely result in 20 mins worth of useful programming and 3 hours 40 of obscure FX combinations. You can see how the Two Ps relate to each other in this example of real world lighting programming practice.

Other Lighting Applications

The examples above relate to programming on a specific kind of show, but we can bet you are already thinking of ways in which Parkinson’s and 80/20 relate to work you have done or situations in which you find yourself. Once you know about these two concepts, they seem to spring up out of every situation you find yourself in. In the example above, 20% of the programming contributed to 80% of the show – or more. So what about Pareto et al in other lighting situations?

See what you think of these potential Pareto combinations:

- 80% of the rigging process takes up 20% of the time. The rest of the time is spent faffing about with odd stuff and booms.

- 20% of the faults take up 80% of the snagging time.

- 20% of the colour choices are used in 80% of the looks.

- 20% of the rig provides 80% of the value. One word, Molefays. Case Closed.

- 80% of the design is created in 20% of the time. This also relates to drawing the plan.

Using Parkinson’s Law and the Pareto Principle in lighting practice

So, now we have started to look for instances in our own practice, the next step is to do something about it. What can we do? Here are some ideas:

- Shorten scheduled time for tasks. Decide to stop programming at a certain time, for example. Go to catering. Don’t create time that you can then waste.

- Avoid half-working on stuff. Either work or don’t. (Do. Or Do Not. There is no ‘try’). If you are half-working is it because you don’t really know what needed doing next? Fine, make a plan/list. Are you subconsciously fitting in with the schedule?

- Be aware of pre-programming sessions using a visualiser. It could be a route to un-productive programming via an extension of the time available to waste. The result can a be a mess to deal with on the day.

- Decide on EXACTLY what you actually need to rig/do/program in order to get this show to an acceptable standard. For programming, make a list and check them off as you go.

- Try to work out which activity is taking you 80% of the time, for only 20% of the result. Address that and consider what the consequence of just not doing it would be. I mean, really not doing it at all.

There is a lot more to getting the best from ideas behind the application of Parkinson’s Law and the Pareto Principle to production lighting practice, this is just a taster to get you thinking. The principles look different across scenarios and between genres as each has its own signature series of tasks and behaviours. Touring and One-Nighters are obviously not going to be exactly the same. The key takeaway here is that time applied to something and the final results are not as closely correlated as the protestant work ethic would have you believe. Be critical of your approach to programming and other lampie tasks.

If you have any examples of Parkinson’s or the Pareto Principle from experiences in your own lighting world, stop by and share them in the comments section.

Rob Sayer HND PGDip FHEA is a Senior Lecturer in Technical Theatre Production, mentor, and consultant in stage lighting and education. As a professional lighting designer, Rob designed and programmed theatre performances, music festivals and large corporate events for blue chip companies while travelling all over Europe. With a background in theatre, he combines traditional stage lighting knowledge alongside fast moving lighting and video technology in the world of commercial events.

Thanks, lot of insightful stuff, it put words on some thoughts I have had when comparing how much time I use at two different venues with almost identical setups. One place I have one hour and it works out fine, even have time for a sandwich and a chat with the bands. The other I always find myself stressed, skipping the free meal and then performing worse.

Really interesting examples, Beau. Cheers.