In the stage lighting calendar, the Christmas season is awash with choirs and orchestras, carol concerts and recitals. On Stage Lighting considers how to light a classical concert ,an orchestra or choir (while keeping conductors and musicians happy) including a simple rig design without overstage rigging postions.

Such musical events might not call for a huge light show of Wobbli Buckettes a-dancing about the place but lighting an orchestra isn’t a walk in the park. Despite what everyone else around you might think, lighting is integral to a successful concert.

In the world of orchestral musicians, “show” lighting is unimportant. Music is all about sound so you can pretty much wave goodbye to any of this “we are all here for the common good” guff – as far classical musos are concerned, you are of no consequence to them. Classical musicians don’t become top class instrumentalists with their ability to see the bigger picture, sometimes leaving you wondering if they would rather even the audience weren’t there.

However, they will know if they can’t see their music in the gloom and are not ones for keeping their troubles to themselves.

The audience, on the other hand, didn’t pay good money just to sit and listen to the CD while not being able to hit “pause” and pop off to the toilet. While not all of the audience delight in watching their favourites warbling or scratching away, seeing the performers is important to the rest and to the management.

Your goal as “person lighting this show” is help the show by making it possible to read dots, not to p**s any musicians off and to light the gig to the satisfaction of the players, concert manager and audience. In the controlled lighting space like a theatre venue or church, there is little ambient light so you are in charge of every bit of light needed.

Lighting The Music

A lot of tiny dots all bunched together – musicians cannot play properly without well lit music. While pit orchestras in theatre use Rat stands (music stands with a built in light), most classical players need a more “comfortable” dot reading environment. Your primary lighting concern should be to enable the musos to read their music easily but you can’t just issue the entire choir with Petzl headtorches – it’d be too expensive for a start.

Lighting the Conductor

The Maestro needs to be lit so the ensemble can see the frantic arm waving that makes sure everyone gets to the end of the tune at the same time. Being able to see music and conductor comfortably is pretty much 90% job done. You might also consider front lighting the maestro for the curtain call, so bows can be taken and flowers received.

Lighting for the Audience

Unlike theatre, intelligibilty of the spoken word is not a big issue but the audience have paid good money to see the show so it would be nice to be able to actually see their favourite artistes at it, a bit of low intensity front light “filling in” helps.. You can also push up the frontlight when it comes to bows and flowers time.

Arty/Mood Lighting. While some Musical Directors will request different colours, moods or textures, we won’t be going into how to achieve this today. The arty stuff comes down to whatever suits the performance which with 90% of these gigs is “Open white and leave it alone” to be honest

Lighting an Orchestra – Know Your Enemies

No, I don’t mean musicians – lighting enemies. The things that are most likely cause members of the ensemble to raise their hand are shadows and glare. Shadows on the page make it harder to read the score – the contrast between the white page and the black notes should be good. Uneven contrast on the page makes the eye work hard and if shadows move (like a violinists bowing arm or a percussionist arms), even harder.

Note about shadows: A light source and an object on stage create a shadow. There is a myth that adding more light sources cuts down on shadows, in fact they just increase. More light sources can mitigate the contrast effect of shadows but can also make them more complex to control. And controlling shadows is our goal, we’ll look into that further on.

Glare in the eyes of the players or conductor is a potential problem. While having lights shone in your face is uncomfortable it also effects the iris of the eye, making it smaller and harder to read music on the page.

We know some potential problems are and how they are caused, so avoid them from the start. Otherwise you will spend your time fielding complaints about the lighting and others will lose confidence in your lighting abilities. Once that happens, the world finds problems even where none exist.

Let’s look look at the practicalities.

Lighting The Scores

To light a choir and orchestra so that they can read their scores with minimal shadow or spill, you would like to use height. Putting your lanterns high up overhead and pointing them straight down means no light in anyone’s eyes, audience or orchestra. It also gives you the smallest, most controllable shadows (if you stand under an overhead light in your house and look down at your feet, you’ll see what I mean). The lower the angle of a light source, nearer horizontal like a sunset, the longer and more unmanagable the shadows become and the longer a shadow is on stage, the more performers it troubles.

The downside of heavy “toplight” is that it can make your ensemble look like they’re being beamed down from an alien spacecraft. A lot of harsh hotspots on the tops of heads and scary gaunt faces. It is also not always possible, quite a lot of concerts setups don’t have the overstage lighting positions required for these angles.

Your options are to bring the toplight a) slightly forward or b) slightly backward. Steep frontside top light can still seem pretty harsh from the audience, especially at levels that light up the music well. Steep backlight can light music while avoiding the hollow faces and foreheads that are too “hot”.

The trouble with steep backlight (directly from straight on upstage) is that, particularly for standing choirs, each persons head throws a shadow directly onto their score. For seated musicians, this is less of a problem. Lighting choirs, this can be eased by moving the steep backlight to one side and adding another backlight from the opposing angle – effectively lighting over each singers shoulder. Any shadow caused by a choir members neighbour is mitigated by the light from the other side.

Lighting the conductor is pretty uncomplicated, the orchestra needs enough to be able to see the stick and any facial expressions used to drive the piece. Light could come from upstage ish but mustn’t fly off into the eyes of the front row. Again, bring the angle steeper (more overhead) or from the side as an alternative. If there are no rigging positions overstage to light the conductor, see if you can find a cross light angle that is not going to bother the audience or the players.

Ok we’ve looked at ways of lighting musicians scores and the man with the stick, what about seeing them from the stalls? To be seen from “out front” we need to add some lighting from somewhere in front of the target (muso, singer, harpist etc). This could be from good old fashioned theatre style front light 45 degrees up and 45 degrees apart, but there are other positions that fill in here. The important thing to remember is that our biggest problem here is going to be “lights in the eyes” of players facing the conductor. This often makes the 45 degree angle less than attractive – a cello player sat in the front row will be guaranteed a front light in the face while trying to see the baton.

A more front/side or side light position fills in faces and is less of a nuisance for the majority. In a horseshoe setup, the players most likely to have the sidelight in their faces are sat either side of the conductor, facing the sidelight position. Just bear this in mind when focussing and cut off top edges at chest height on the opposite side to mitigate glare for the those facing.

The principle with this front light, is that that unlike a traditional theatre method for lighting a stage, the front light is Fill lighting that will be used at a lower intensity. If you are lighting the scores with positions from both sides of the stage, the sidelight provides most of the brightness required to see the orchestra from the back row of the audience.

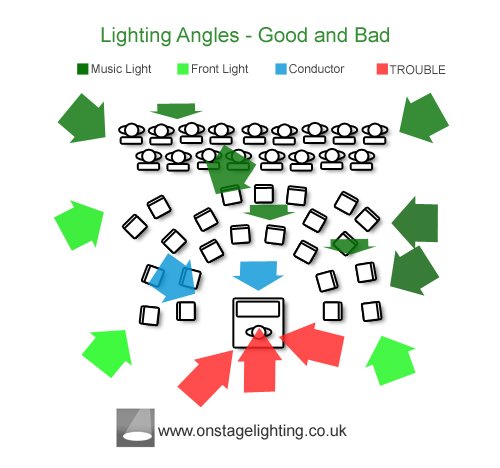

Looking at the image, you can see lighting angles that are useful marked in green while red ones are going to cause problems. The arrows are not fixture positions but indicate direction with stubby ones being steeper (from over stage). As the graphic shows, any lighting angle that travels straight into the face of a player, particluarly via the conductor, is to be avoided. The angles that travel from upstage to down vary according to venue design, just make sure that audience members are not in the firing line when shooting from lower rigging positions.

Lighting a Concert in Reality

Many church recitals and school carol concerts are in venues that aren’t “the ideal world”. So, having looked at how we would really like to light our concert, let’s look at a common setup. Makeshift concert spaces often have no facility for rigging overhead, making wind-up lighting stands the only option.

We don’t have option to use high fixture positions overhead to light our orchestra – we need to be clever and even more aware of our angles, shadow and spill. Common wind-up stands go to a maximum height of 3-4 metres, a lot of our lighting angles are going to be shallower than we might prefer.

The benefit to portable stands is that we can place them pretty much where we like around the perfomance area – within reason. The other key to success is using a decent number of focussable fixtures with barndoors. 650W or 1000w fresnels are fine, depending on the size/throw of the venue ( 750w Source Four PARs/ PARnels are common in my world). The final piece of the puzzle is to use a number of stand positions to get “localised” light around the stage.

The first example here is scaled down version of a setup I have used regularly to light a choir and orchestra. The actual rig version uses double the number of fixtures to cover a larger area, but here we’ll use 12 fresnels for simplicity of demo and to allow for the smallest of budgets. We will pretend that the choir is also stood on one level. Tiered staging is often a feature of professional choir setups. Ideally, each lantern should be individually dimmed to allow for the maximum intensity control. Pairing two fresnels on each stand, while convenient, can cause intesity problems expecially as often the fixtures are working on different tasks and throw distances.

Looking at the diagram, one the lights on one side are numbered (the opposite partner of each lantern performs the a mirror task).

- Light 1 provides some front face lighting and a bit of light for the conductors stand. This is the danger angle that you probably won’t want to use too much apart from the walk-on and calls.

- Light 2 provides music sidelighting for the DS ensemble members facing across stage, lighting their music AND creating friendly front light for the players on that side of stage.

- Light 3 does slightly back lighting for the next US set of musicians. It also lights the conductor for the players.

- Light 4 side lights along the next row and a bit of front fill for the opposite side choir ranks.

- Light 5 creates front fill across the back ranks and is at an angle that troubles no one.

- Light 6 cross lights the rear rows of the choir ranks, far side. Music light, enough for 2 or 3 rows if you’re lucky.

Focus Notes:

Like most lighting, it’s all in the focus.

The FOH face lights are the worst offenders for “in the eyes lighting” of the opposite musos. Don’t forget to run them at a low intensity during the show, you can whack them up for the curtain calls.

Any light going downstage of the conductor must be cut off the front row of seating at chest height. Barndoor off to suit . Although the conductors face is important to the players, you can cheat this by top dooring lower. There is often enough bounce from the score to see him grimacing.

Downstage crosslight/conductor sidelight – watch the DS b/door and long door off the audience seated.

Far cross lighting along the singers should be top doored off to just above head height on the other side of stage. This sidelight is going to be lighting faces as well as music.

Near lighting fresnels will need to be as wide as poss. Spot the far lighting ones down a touch to get a bit more oomph out of them.

You can let all US back/side lights light as far downstage as they go unless you think that their shadows are going to be a nuisance. Look out for the eyes of any front row audience and the two most downstage musicians.

Keep all barndoors tidy– every door should be in to at least the start of the visible beam.

Check light levels on stage by holding your hands out, squatting down and generally doing things that approximate where the scores and seated players will be. You can’t predict where every shadow will come from when a stageful of players appear, but you know you’re on the right track.

While the basic 12 light version of lighting an orchestra is simple, it’s a pretty blunt instrument that will only really cut it on a smaller orchestra and a handful of singers. A larger ensemble and some tiered risers for the choir mean you could do with some more fresnels (18-20) and a some larger wind-up stands or extensions that lift our rig higher , 4 – 5 meters should give the additional height to accommodate the rear riser lift. But the principle remains that same.

What next? Orchestra Rehearsals

Having set up the kit and a rough focus (often known as the focus in these situations) you await the influx of odd shaped intrument carriers, the rustle of scores and the sharpening of the conductors baton – the orchestra arriving for rehearsals. With any luck you have done your job so well that, after ascertaining that everything is good for them, you can slink off for a cup of tea. But how do you know if your lighting is to the choirs satisfaction?

Although you’d probably like the world to know that you are lighting the show, it is better not to make yourself to obvious and keep a safe distance, while watching players unpack and set up their music. You can easily tell if someone is uncomfortable or having trouble with the light levels on their scores. Often, musicians will adjust their chair position or rearrange their stands to get rid of unwanted bow shadows and you should let them get on with it. Only get involved at the behest of the conductor when there is something that only you can solve.

There is a rule amongst technicians that you never ask a musician if they are OK – they feel the need to find something to give you as an answer which is likely to result in pointless work on your part. Avoid direct questions like that. I usually prowl around the ensemble for a few minutes early in the rehearsal to see for myself if I would be happy with the light levels on each music score.

On a recent show, during this prowl I noticed that the organist had moved the organ into a position that meant no significant direct light was lighting his music. I quietly approached him in a break to see if he needed an Anglepoise or to move his intrument. We discussed the possibilities and he decided in the end that he didn’t want an Anglepoise for fear of knocking it overe during the show, and was happy to live with the light levels as they were. The guy was amazed that someone cared about his personal comfort that, despite my stupidity of breaking the golden rule, it was resolved by his rare “make-do” attitude.

If anything really needs adjusting, you obviously can’t clatter around with ladders during rehearsals so it must wait until rehearsals are over unless the problem is too intrusive to continue. For now, the orchestra and conductor just need space to get on with their bit.

After rehearsal, you can get on with whatever jobs you have left to do. But there is one more person you have to consider, now the orchestra have gone: The Tuner. There are two things that make their life harder – a lot of noise and working in the dark. If you have stuff to do, leave a light for the tuner to work by and keep the clatter of ladders to a mininum. They’ll finish much quicker.

All Done

Hang on Rob, what about the show?

As an On Stage Lighting reader, I am sure you have the show under control. The thing about lighting an orchestra or choir concert is that the rehearsals are the break point. A successful gig in this case is getting to the end of rehearsals with no questions about dimly lit music, glare or your focus.

After that, the show is just the thing between you and the load out.

Rob Sayer HND PGDip FHEA is a Senior Lecturer in Technical Theatre Production, mentor, and consultant in stage lighting and education. As a professional lighting designer, Rob designed and programmed theatre performances, music festivals and large corporate events for blue chip companies while travelling all over Europe. With a background in theatre, he combines traditional stage lighting knowledge alongside fast moving lighting and video technology in the world of commercial events.

An excellent primer, Rob.

The only thing I can add is that, where you can’t avoid the face-light annoying the cellos and second violins, it’s worth slipping half a cut of 156 to ‘soften’ the glare.

And to put the subject in direct context, for a recent chamber orchestra concert, I used three times the number of fixtures to provide down- and side-light for the musicians (plus a little from US onto the conductor) than face-light for the audience to see the turns.

Next up: how to light a piano recital with just two fresnels…

Thank you for an excellent informative piece, and for other equally good down to earth bits on your site. I’ve been lighting youth group performances as an amateur for 30 years, and still use a kit of about 20 Rank Strand lights (including a couple of pattern 60s) and a 12-way Mini-2+ control and packs, and have managed to do umpteen different shows with that: last year it was ‘Sound of Music’! I’m tempted to add a few more lamps, but I’m not sure I really need them…

Keep up the good work.

Hi J B, thanks for your kind words. If you’re still using P123s or P743s you will appreciate what good lanterns they were/are. “You can do plenty with twenty”. :D

Now look here Rob – lighting orchestras is supposed to be one of my specialities and now you have gone and made it look all easy!

I’ve been lighting orchestras for many years. This is the best article I’ve seen on this subject. I look forward to sharing this with my colleagues here at Centre In The Square and the Kitchener Waterloo Symphony. Thanks.

This is a very good and comprehensive summary of the problems that come with orchestra lighting in my experience.

Two points I would add – first soloists. They really need light from the audience perspective, and classical soloists are usually placed so they can see the conductor. That means they are so close to the orchestra there is little chance of the spill missing the orchestra players, and often the leader of the orchestra. It is a good approach to go to the players and explain that if you move the light you just move the problem to another musician. They need to put up with it or move back. Usually they put up with it when they realise why the light is there.

Second – period instruments. Older instruments such as Harpsichoprds are not so good at stability with changing temperatures. Get the lights on early and leave the levels alone. And speak to the players about it – they will appreciate your concern.

Finally, keep all your creative ambitions for everything off the stage. Classical concerts benefit from colour and design as much as any other – just not on the musicians!

Love this article, the same mindset of classical musicians translates to sound technicians too!

A orchestra is basically a strip club right